“To these grievous measures, Americans cannot submit.”

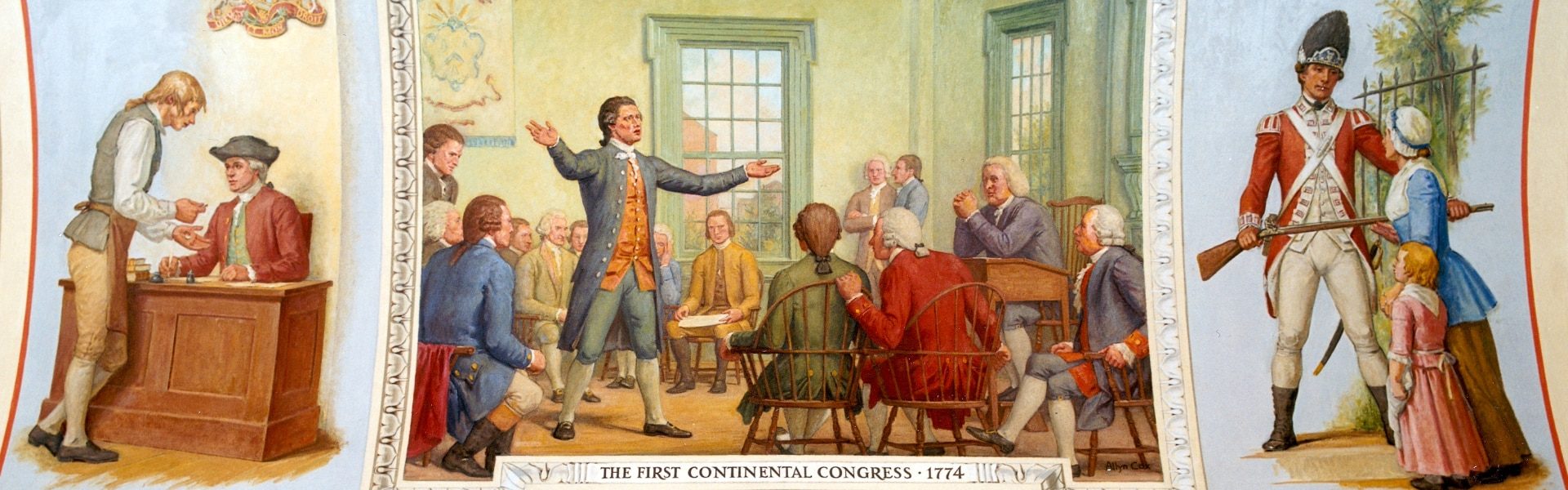

That bold declaration helped spark coordinated resistance across the colonies in 1774. Today marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration and Resolves of the First Continental Congress, passed unanimously on October 14, 1774.

Almost forgotten today, the Declaration and Resolves were a precursor to both the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights. It reaffirmed that acts beyond the Constitution are void and must be resisted and nullified.

The first line established that internal taxation, duties, and “unconstitutional powers” stemmed from the broader Declaratory Act of 1766, where Britain claimed power over the colonies “in all cases whatsoever.”

“Whereas, since the close of the last war, the British Parliament, claiming a power of right to bind the people of America, by statute, in all cases whatsoever, hath, in some Acts, expressly imposed taxes on them, and in others, under various pretences, but in fact for the purpose of raising a revenue, hath imposed rates and duties payable in these Colonies, established a Board of Commissioners, with unconstitutional powers, and extended the jurisdiction of Courts of Admiralty, not only for collecting the said duties, but for the trial of causes merely arising within the body of a County”

The Declaration asserted ten fundamental rights founded in “the immutable laws of nature,” including life, liberty, property, and the right to assemble.

It also listed grievances, including depriving Americans of trial by jury, standing armies in peacetime, and especially the Coercive Acts, also known as the Intolerable Acts by many today.

The Coercive Acts, passed by Parliament from March to June 1774, aimed to punish Massachusetts for the Boston Tea Party. Instead of dividing the colonies, they united support for Massachusetts, as it was widely accepted that arbitrary power unchecked could easily spread and expand.

It was the first of the Coercive Acts – the Boston Port Act – that started the drive to call a “grand continental congress” in the first place. Passed by Parliament on March 31, 1774, the act authorized the Royal Navy to blockade Boston Harbor because “the commerce of his Majesty’s subjects cannot be safely carried on there.”

The blockade commenced on June 1, 1774, effectively closing Boston’s port to commercial traffic. Additionally, it forbade any exports to foreign ports or provinces. The only imports allowed were provisions for the British Army and necessary goods, such as fuel and wheat. The Act mandated that the port remain shuttered until Bostonians made restitution to the East India Company (the owners of the destroyed tea), the king had determined that the colony was able to obey British laws, and that British goods once again could be traded in the harbor safely. However, if the Bostonians refused to pay the East India Company or the king remained unsatisfied, the harbor would be blockaded indefinitely.

In short, it was an act of collective punishment that united the opposition.

When word of the Act hit Boston on May 11th, the Sons of Liberty sprang to action. A town meeting led by Dr. Joseph Warren and moderated by Samuel Adams passed a resolution calling on all the colonies to “stop all importation from Great Britain, and exportations to Great Britain, and every part of the West Indies, till the Act for blocking up this harbor be repealed.”

Paul Revere was immediately dispatched to take the resolution to committees of correspondence in other colonies. The New York committee acted quickly – and responded to Boston:

“The alarming Measures of the British Parliament relative to your ancient and respectable Town which has so long been the Seat of Freedom fill the inhabitants of this City with inexpressible Concern. As a Sister Colony suffering in Defence of the Rights of America we consider your Injuries as a common Cause to the Redress of which it is equally our Duty and our Interest to contribute.”

While they didn’t immediately halt trade, they pushed for a Congress of the colonies to coordinate a response:

“We conclude that a Congress of Deputies from the Colonies in general is of the utmost Moment that it ought to be Assembled without Delay, and some unanimous Resolutions formed in this fatal Emergency not only respecting your deplorable Circumstances but for the Security of our common Rights.”

By July, twelve colonies agreed to a “grand continental congress,” set for September 5 at Carpenter’s Hall in Philadelphia. Only Georgia did not send delegates.

When Congress met, debates emerged immediately, such as Patrick Henry’s argument against equal voting for all colonies, “it would be great Injustice, if a little Colony should have the same Weight in the Councils of America, as a great one.” On the other side, Major John Sullivan of New Hampshire observed “that a little Colony had its All at Stake as well as a great one.”

In that debate, Sullivan and his allies won – a precursor to the debates over a federal vs a national system in the years to come – and it was agreed that it would be one vote per colony.

But, on Sept. 6, news arrived from Boston of a massive military attack by the British. As John Adams noted in his diary, “Went to congress again. Received by an express an Intimation of the Bombardment of Boston—a confused account, but an alarming one indeed.—God grant it may not be found true.”

Robert Treat Paine also wrote about the alarming news in his diary:

“About 2 o Clock a Letter came from Israel Putnam into Town forwarded by Expresses in about 70 hours from Boston, by which we were informed that the Soldiers had fired on the People and Town at Boston, this news occasioned the Congress to adjourn to 8 o Clock pm. The City of Phila. in great Concern, Bells muffled rang all pm.”

In response, when Congress came back into session that evening, Patrick Henry opened with what is now one of his many famous quotes, “The Distinctions between Virginians, Pensylvanians, New Yorkers and New Englanders, are no more. I am not a Virginian, but an American.”

Here, Henry was urging the other delegates to set aside their differences and come together in the aid of their brothers and sisters in Boston, under military bombardment, they thought, at that very moment.

Turns out it was a rumor – but the event, today known as the “Powder Alarm” (covered in detail in this podcast) showed the colonists were serious about taking action in defense against the British.

Congress got to work, establishing committees to define colonial rights and detail how Parliament’s acts violated those rights and harmed the economy.

In the meantime, Paul Revere arrived at Congress on Sept. 16 with another urgent dispatch from Boston. This time with a copy of the Suffolk Resolves, primarily authored by Joseph Warren and passed on September 9th. They called for a boycott of British imports and goods, non-compliance to the Coercive Acts, disobedience to courts, tax resistance and more.

Further, the Resolves urged Suffolk communities to raise a militia “to learn the arts of war.” According to the record, there was a wild applause at the end, and even though conservatives like Joseph Galloway weren’t happy with what they considered “a complete declaration of war,” the Resolves were passed by a unanimous vote in the first official act of the Continental Congress.

By the time the Declaration and Resolves were taken up, there was little opposition to moving forward with the Declaration of Rights, or the list of Grievances, which included the Sugar Act of 1764, the Currency Act of 1764, the Townshend Acts of 1767, the Coercive Acts of 1774 – and more.

In the last of the grievances, Congress rejected the militarized enforcement of these acts as well:

“The keeping a Standing Army in several of these Colonies, in time of peace, without the consent of the Legislature of that Colony in which such Army is kept, is against law.”

Closing the Declaration and Resolves of the First Continental Congress was this powerful message:

“To these grievous Acts and measures Americans cannot submit.”

They followed up the next week with the first of the founding four documents, The Continental Association, a voluntary agreement that put teeth into the Declaration and Resolves – and the Suffolk Resolves, by formalizing a coordinated economic embargo on British goods.

At the close of the Congress, John Adams shared with Patrick Henry a letter he received from Major Joseph Hawley of Northampton containing “A few broken Hints” as he called them, of what was proper to be done in response to the British aggression. Adams recalled the interaction:

“This Letter I read to Mr Henry, who listened to it with great attention and as soon as I had pronounced the Words “After all We must fight” he erected his Head and with an Energy and Vehemence that I can never forget, broke out with “By God I am of that Mans Mind.” I put the Letter into his hand, and when he had read it he returned it to me with an equally Solemn Asseveration that he agreed entirely in Opinion with the Writer.”