Equifax, which knows more about you than your own mother, (1) failed to maintain its servers, (2) was hacked and lost sensitive personal data for 143 million people, (3) concealed that fact for months, (4) blamed another company for the problem, then (5) finally admitted it caused the problem. To make matters worse, after the hack but before disclosing it, three executives sold off nearly $2 million in Equifax stock.

“What should I do to protect myself?” is a difficult question to answer. The Federal Trade Commission put up a page recommending checking your credit reports, placing a credit freeze, placing a fraud alert, and filing your taxes early so that a scammer doesn’t file them for you and obtain your tax refund. Brian Krebs has a much more thorough FAQ over here.

To call this situation “frustrating” would be an understatement. Virtually everyone with a credit history now bears the burden of making sure their own identity is safe due to Equifax’s negligence. People have already filed class-action lawsuits, and rightly so.Data breaches are depressingly common. According to the Privacy Rights Clearinghouse, in 2016 alone, there were 397 publicly-disclosed hacking or malware breaching incidents. Every year, around 70 data breach security class actions are filed against companies ranging from email providers to health insurers to restaurants. The cases involve everything from medical information (which is among the most valuable on the black market) to email addresses to Social Security numbers.

It is no simple matter to sue a company for losing your sensitive personal information. The cases raise issues of standing, pleading, proximate causation, class certification, common-law tort limitations, state statute interpretation, and damages calculations that would send a law student running from the classroom and into the safety of the job as a barista (where their data would be stolen anyway, like in the Krottner case discussed below). That is also why this post is so long and filled with conflicting case law.

If you want the TL;DR (“too long; didn’t read”): the most likely outcome is that, after several years of difficult litigation and objections to settlements and appeals of those objections, Equifax will agree to better corporate security procedures, provide credit monitoring, identity theft insurance, and fraud resolution services, along with compensation for documented damages up to $10,000 and a modest cash payment in the realm of $50. The lawyers representing the consumers and the lawyers representing Equifax will spend hundreds of thousands of hours on the case. The lawyers for Equifax will probably make millions of dollars, paid monthly as they send their bills to Equifax, and the lawyers for the consumers will also probably make millions of dollars at a comparable hourly rate but paid at the very end of the case. (What I described above is essentially what happened in the Anthem data breach security litigation, the most comparable example we have to the Equifax situation.) After questions of standing and class certification, perhaps the most critical question is whether Equifax violated the Fair Credit Reporting Act with its poor information security, and if that violation was “willful.” If so, then Equifax is on the hook for no less than $100 but no more than $1,000 for each violation.

If the protracted path the lawsuits will likely take towards a reasonable settlement strikes you as absurd, you’re not alone. I think it’s absurd. I think Equifax should swiftly conduct an investigation, open its records to the plaintiffs’ lawyers and their experts, and then offer the settlement I described above. But I doubt they’ll do that. Instead, they will probably raise each and every objection they can, dragging out the litigation and driving up the hours that the plaintiffs’ lawyers have to put into the case, so that every single victory for consumers in the case, no matter how slight, will have to be hard won. I hope I’m wrong, but this is what past cases teach us. This post outlines some of the many fights that will arise in the case and explains how the eventual settlement of the case will likely look.

How Was Equifax Hacked?

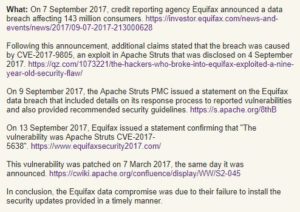

For all the allure surrounding “zero day” exploits, in which a nefarious attacker discovers an unknown vulnerability in software, most computer security breaches are much more banal. Most unauthorized access involves either the use of phishing scams to trick people into revealing their passwords or known vulnerabilities in software that users or administrators failed to update in a timely manner. The Clinton campaign emails that were released by Wikileaks were obtained by way of a phishing scam directed at her campaign chairman, John Podesta. The WannaCry ransomware cryptoworm involved a known Windows vulnerability that had been patched two months before WannaCry was released. In the case of Equifax, the hack happened because Equifax failed to timely update its servers to correct a known vulnerability.

Equifax was hacked between May and July 2017, discovered the unauthorized access on July 29, 2017, then on September 7, 2017 revealed it had lost “names, Social Security numbers, birth dates, addresses and, in some instances, driver’s license numbers,” as well as “credit card numbers” and “dispute documents with personal identifying information.” Equifax first blamed the Apache Software Foundation by claiming the hack involved a previously-undisclosed vulnerability in the software, but then had to admit that the hack actually used a vulnerability that was already discovered and fixed by Apache in early March 2017. Equifax had simply not installed the security updates:

Over time, more information about the hack will be uncovered and disclosed. For example, why wasn’t the data encrypted or otherwise protected against an attack, and why was Equifax holding onto historical credit card data? After the breach, security researchers started poking around Equifax’s websites and noticed absurd problems, including a database protected by the account “admin” with the password “admin.” As it stands now, this already looks like textbook negligence. Equifax failed to do what millions of regular people do all the time: update their software to ensure that the latest security vulnerabilities have been patched.

How Many Equifax Lawsuit Have Been Filed?

More than thirty class actions have been filed so far, and it is likely that many more will be filed in the near future. Most of these will be filed in federal court, and a petition is already pending with the United States Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation, a group of federal judges that decide whether or not all of the cases across the country in federal court should be “consolidated” into a single case for pretrial purposes. In all likelihood, that petition will be granted, just as it has been granted in prior data breach security litigations, including Ashley Madison, Anthem, Home Depot, Target, Zappos, and Sony.

That sort of consolidation is generally a good thing. It makes no sense to have multiple federal courts across the country all dealing with the same issues, which is wasteful and can create conflicting legal decisions. Consolidation also allows the court handling the cases to create a Plaintiffs’ Steering Committee, a group of court-appointed lawyers representing the consumers, so that there aren’t endless fights among different lawyers with different clients in different lawsuits. (I’m on two Plaintiffs’ Steering Committees in other litigations.)

That consolidation, however, would not affect class actions in state courts, so long as those class actions were not removed to federal court either because of the Class Action Fairness Act or because of a lack of personal jurisdiction over Equifax in states other than Georgia (where Equifax, Inc., is incorporated and where it has its principal place of business. (Don’t get me started on either of these issues, in my humble opinion they are both just ways to tilt the court system in favor of large corporate defendants.)

These Are Open-And-Shut Cases, Right?

Alas, no. Equifax, like every other corporate defendant that stupidly exposes your data to scam artists, has a multitude of defenses available thanks to years of anti-consumer court decisions.

I’ve written about class action lawsuits many times in the past, and how the courts have made it particularly difficult for any sort of consumer class action to succeed, like when the Supreme Court made it harder to certify class actions with Comcast v. Behrend. For this post, however, I will stick to privacy and data breach related cases.

Do You Have Standing To Sue Equifax For Losing Your Personal Information?

We start right at the top with the United States Supreme Court and Spokeo, Inc. v. Robins, a class action involving a “people search engine” that (allegedly) provided inaccurate information about people in violation of the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FRCA). In May 2016, the Supreme Court held that, to file a lawsuit (in legal jargon, to show standing) a plaintiff had to show an injury-in-fact by way of “concrete and particularized” injury that is “actual or imminent, not conjectural or hypothetical.”

The case was hailed by corporate defendants because it appeared to further limit the ability of consumers to bring class actions. Nonetheless, on August 15, 2017, the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit released its new opinion in the case, finding that the plaintiff had indeed adequately alleged standing because the FCRA was meant to protect concrete interests and the alleged violations of it harmed those interests. We don’t know yet if the Supreme Court will review the case again and change the rules again.

The very first thing that defendants like Equifax argue is that consumers whose data was lost don’t have standing to sue for the loss of their data, because the threat of a future identity theft is not a “concrete and particularized” injury-in-fact that is “actual or imminent.” Some legal commentators and courts have said that the Circuit Courts have developed a split over this issue, with some courts finding standing and other courts denying it, but I’m not so sure. I think a close look at the facts of each case reveals several patterns:

- Krottner v. Starbucks Corp., 628 F.3d 1139, 1142–43 (9th Cir. 2010) (finding standing for employees’ increased risk of future identity after theft of a laptop containing the unencrypted names, addresses, and social security numbers of 97,000 Starbucks employees)

- Reilly v. Ceridian Corp., 664 F.3d 38, 40, 44 (3d Cir. 2011) (plaintiff-employees’ increased risk of identity theft theory too hypothetical and speculative to establish “certainly impending” injury-in-fact after unknown hacker penetrated payroll system firewall, because it was “not known whether the hacker read, copied, or understood” the system’s information and no evidence suggested past or future misuse of employee data or that the “intrusion was intentional or malicious”).

- Katz v. Pershing, LLC, 672 F.3d 64, 80 (1st Cir. 2012) (brokerage account-holder’s increased risk of unauthorized access and identity theft theory insufficient to constitute “actual or impending injury” after defendant failed to properly maintain an electronic platform containing her account information, because plaintiff failed to “identify any incident in which her data has ever been accessed by an unauthorized person”)

- Remijas v. Neiman Marcus Grp., 794 F.3d 688, 693 (7th Cir. 2015)(finding standing for a claim based on the risk of future identity theft, noting, “Why else would hackers break into a … database and steal consumers’ private information? Presumably, the purpose of the hack is, sooner or later, to make fraudulent charges or assume those consumers’ identities.”)

- Galaria v. Nationwide Mut. Ins. Co., No. 15–3386, 663 Fed.Appx. 384, 387–89, 2016 WL 4728027 (6th Cir. Sept. 12, 2016) (finding standing for consumers’ increased risk of future identity theft because “[t]here is no need for speculation where Plaintiffs allege that their data has already been stolen and is now in the hands of ill-intentioned criminals”)

- In re Horizon Healthcare Servs. Inc. Data Breach Litig., 846 F.3d 625, 641 (3d Cir., January 20, 2017)(In a case involving the theft of two laptops from a health insurer which contained personally identifiable information and protected health information, “Our precedent and congressional action lead us to conclude that the improper disclosure of one’s personal data in violation of FCRA is a cognizable injury for Article III standing purposes.”)

- Beck v. McDonald, 848 F.3d 262, 277 (4th Cir., Feb. 6, 2017), cert. denied sub nom. Beck v. Shulkin, 137 S. Ct. 2307 (2017)(“We acknowledge that the named plaintiffs have been victimized by at least two admitted data breaches. … But absent a sufficient likelihood that Plaintiffs will again be wronged in a similar way these past events, disconcerting as they may be, are not sufficient to confer standing to seek injunctive relief.” Internal quotations omitted).

- Attias v. Carefirst, Inc., 865 F.3d 620, 628 (D.C. Cir. August 1, 2017)(finding standing because “an unauthorized party has already accessed personally identifying data on CareFirst’s servers, and it is much less speculative—at the very least, it is plausible—to infer that this party has both the intent and the ability to use that data for ill.”)

As the Eighth Circuit held in a data breach security case just two weeks ago, “These cases came to differing conclusions on the question of standing. We need not reconcile this out-of-circuit precedent because the cases ultimately turned on the substance of the allegations before each court.” In re SuperValu, Inc., No. 16-2378, 2017 WL 3722455, at *4 (8th Cir. Aug. 30, 2017)(finding standing for plaintiffs whose identity had been stolen, but denying standing for others because, among other reasons, “the allegedly stolen Card Information does not include any personally identifying information, such as social security numbers, birth dates, or driver’s license numbers.”)

The Beck case decided earlier this year explains the differences between the outcomes:

Underlying the cases are common allegations that sufficed to push the threatened injury of future identity theft beyond the speculative to the sufficiently imminent. In Galaria, Remijas, and Pisciotta, for example, the data thief intentionally targeted the personal information compromised in the data breaches. Galaria, 663 Fed.Appx. at 386, 2016 WL 4728027, at *1 (“[H]ackers broke into Nationwide’s computer network and stole the personal information of Plaintiffs and 1.1 million others.”); Remijas, 794 F.3d at 694 (“Why else would hackers break into a store’s database and steal consumers’ private information?”); Pisciotta, 499 F.3d at 632 (“scope and manner” of intrusion into banking website’s hosting facility was “sophisticated, intentional and malicious”). And, in Remijas and Krottner, at least one named plaintiff alleged misuse or access of that personal information by the thief. Remijas, 794 F.3d at 690 (9,200 of the 350,000 credit cards potentially exposed to malware “were known to have been used fraudulently”); Krottner, 628 F.3d at 1141 (named plaintiff alleged that, two months after theft of laptop containing his social security number, someone attempted to open a new account using his social security number).

Here, the Plaintiffs make no such claims. This in turn renders their contention of an enhanced risk of future identity theft too speculative. On this point, the data breaches in Beck and Watson occurred in February 2013 and July 2014, respectively. Yet, even after extensive discovery, the Beck plaintiffs have uncovered no evidence that the information contained on the stolen laptop has been accessed or misused or that they have suffered identity theft, nor, for that matter, that the thief stole the laptop with the intent to steal their private information.

Beck v. McDonald, 848 F.3d 262, 274 (4th Cir. 2017). That is to say, the mere possibility that maybe someone could have taken the sensitive personal information is not enough. But where it appears that sensitive personal information was actually accessed, particularly where the circumstances suggest a motive to use the information improperly, there is standing to bring a claim relating to the threat of future identity theft.

In the Equifax case, hackers broke into the database for a company in the business of possessing and using personally identifiable information and obtained “names, Social Security numbers, birth dates, addresses and, in some instances, driver’s license numbers,” as well as “credit card numbers” and “dispute documents with personal identifying information.” That would likely be sufficient to confer standing on plaintiffs who allege the threat of future identity theft under any of the above cases.

Ironically, the only Circuit Court that doesn’t seem to have grappled with this issue much is the Eleventh Circuit, which is the appellate court for the Northern District of Georgia, the federal court where Equifax is based, and where the current petitions for consolidation have argued the cases should be heard for pre-trial purposes. The closest they came to the issue was Resnick v. AvMed, Inc., 693 F.3d 1317 (11th Cir. 2012), which found standing for plaintiffs who had already been victims of identity fraud. There’s a good chance, however, that the Eleventh Circuit will rule on these issues before the Equifax case reaches them, because the same issues arose in the Community Health Services data breach litigation, although earlier this year the district court denied the plaintiffs an interlocutory appeal on the issue. We’ll thus have to wait and see what the Eleventh Circuit does.

If Equifax Victims Have Standing, Do They Have A Claim?

At first blush, this seems ridiculous: of course the victims have a claim! Alas, the law is not so simple. There is no single “data breach” claim.

In data breach security lawsuits, the most commonly alleged claim is negligence, the same common law state tort used for car accidents, slip-and-falls, and dog bites. Negligence involves the defendant breaching a duty it had to the plaintiff and thereby causing the plaintiff harm, the familiar “duty-breach-causation-harm” elements taught to every 1L in law school. The LawFare blog had a post on the duty element earlier this week, collecting a couple cases hostile to the victims of data breaches, like the questionable Pennsylvania Superior court case Dittman v. UPMC, 2017 PA Super 8, 154 A.3d 318, 320 (2017), which inexplicably held it was “unnecessary to require employers to incur potentially significant costs to increase security measures when there is no true way to prevent breaches altogether,” which is akin to holding that there is no true way to prevent car accidents altogether, and so no person can be held accountable for drinking before driving.

Some courts also apply the “economic loss rule,” which prohibits negligence claims where the plaintiff has suffered only financial losses, but not any physical harm. The economic loss rule is more like a slice of Swiss cheese than a “rule,” given the vast number of exceptions recognized by most states, but it can sometimes still preclude negligence claims arising from purely economic losses.

Nonetheless, courts have generally found that most states recognize the legal “duty” necessary to support a negligence claim following a data breach. See, e.g., In re Target Corp. Data Sec. Breach Litig., 66 F. Supp. 3d 1154, 1176 (D. Minn. 2014)(dismissing negligence claims for plaintiffs in Alaska, California, Illinois, Iowa, and Massachusetts, but allowing all other states’ negligence claims to proceed.)

The second most commonly alleged claim is a violation of state consumer protection laws, which come under various names, including unfair and deceptive practices, unfair competition, unfair trade practices, consumer fraud, and so on. Each state has a different consumer protection act, and each state’s courts have interpreted their act differently, so this becomes a prolonged state-by-state analysis raising all of the same issues, such as whether consumers have standing to raise claims involving future threats of harm, whether the act covers data breaches, and whether the act is enforceable by consumers or just by the state attorney general. The opinion in the Target case linked above includes a thorough description of most of these issues, as does the opinion in the Sony case.

After negligence and unfair practices come a whole host of potential claims depending on the states involved, including everything from breach of contract, to breach of implied contract, to negligent misrepresentation, to unjust enrichment, and so on. For each claim, all of the same issues come up relating to standing, duty, and whether or not the claim can truly be used for a data breach case.

The Equifax situation, however, opens up the use of an interesting theory: because Equifax is a credit reporting agency, it is subject to the Fair Credit Reporting Act. Under 15 U.S.C. § 1681e, consumer reporting agencies “shall maintain reasonable procedures designed to … limit the furnishing of consumer reports…” Equifax’s failure to do so could subject them to liability under 15 U.S.C. § 1681n, which creates civil liability for “willful noncompliance” with the FCRA, and 15 U.S.C. § 1681o, which creates civil liability for “negligent noncompliance” with the FCRA. I’ve already seen complaints against Equifax that allege these claims. We can expect to see extensive arguments about whether or not Equifax’s actions constitute “noncompliance” at all, and whether or not that noncompliance was “willful.” Equifax is likely quite worried that, under some interpretations of the FCRA’s “willful noncompliance” statute, there is no need to prove actual damages, and each violation comes with a penalty “of not less than $100 and not more than $1,000.” 143 million times $100 is quite a lot; 143 million times $1,000 is even more. “Section 1681n, which creates the cause of action for willful violations, also does not impose the consequential-damages requirement that defendants wish to add to the statute.” Beaudry v. TeleCheck Servs., Inc., 579 F.3d 702, 705 (6th Cir. 2009).

And, of course, the FCRA comes with its own long trail of complicated case law. An article by two defense lawyers in the American Bar Association’s Business Law Today explained how corporations can use Spokeo and other cases to thwart consumers’ attempts to certify a class action, which would leave each consumer fighting the case on their own.

Here’s the point: to many consumers’ surprise, bringing a claim against a company that negligently lost your sensitive personal information is hardly simple, because there’s no unified “data breach” cause of action, and companies like Equifax use every opportunity they have to limit the number of claims the consumers have.

What Can I Expect From The Equifax Lawsuits?

You can expect to wait. As I mentioned towards the beginning of this post, it would be fantastic if Equifax would swiftly investigate what happened, open up its records to the consumer lawyers, and then offer a reasonable settlement. But that never happens. Instead, defendants challenge standing, challenge the causes of action alleged by the plaintiffs, challenge the certification of a class action, object to the discovery requests made by the plaintiffs (here’s a recent post of mine that goes deep into the discovery “proportionality” standard in the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, and the many ways defendants use it to avoid producing evidence), failed to provide all of the documents they have relating to discovery requests, move for summary judgment, and seek interlocutory appeals before they ever sit down to discuss her reasonable settlement offer. Then, even once a settlement is reached, it has to be approved by the court, a process that can take years itself given the number of objections and appeals that class-action settlements typically raise these days.

As one example of the protracted courses these cases take, Target revealed a security breach in December 2013 and litigation began immediately. Target first entered into a settlement in the consumer class-action cases in November 2015, but several class members filed objections, resulting in an appeal and a remand, and in May 2017 the district court approved the new settlement — but that settlement itself requires approval by the appellate court, so the consumers are still waiting.

So What Kind Of A Settlement Are We Talking About?

The Target settlement, which involved credit card and debit card information along with names, mailing addresses, email addresses, and phone numbers, provided for consumers to be reimbursed for all of their documented losses from the data breach, up to a maximum of $10,000, which is more than anyone in the class could prove they incurred. The average award is likely around $40, and more than 225,000 people submitted claims to the settlement. Assuming the current settlement is approved, Target will reform its data security practices, the class will be paid $10 million total, and the lawyers for the class will be paid around $6.75 million (paid separately from the $10 million).

The Home Depot settlement, which involved 40 million consumers’ payment data and 53 million customers’ email addresses, provided for a $13 million fund for consumers, $6.5 million for internet and “dark web” monitoring services, and $7.5 million in attorney fees.

The proposed settlement in the Anthem data breach security litigation (a settlement which hasn’t yet been approved by the court and which will likely be subject to objections and appeals, too) is somewhat similar, but with some extra credit monitoring. Class members will receive two years of identity fraud insurance, identity theft insurance, and fraud resolution services. Anyone who has their own credit monitoring can receive cash, which will likely be between $36 and $50. Additionally, $15 million will be set aside for class members to accommodate out-of-pocket claims up to $10,000. The lawyers will seek up to $37.9 million for attorney fees and $3 million in reimbursements for costs they spent (we don’t know yet what the court will approve, that’s just the highest the lawyers can request according to the settlement agreement).

A quick fact to think about regarding Equifax: in the Anthem litigation, approximately $23 million (paid by Anthem) will be spent just on giving class members notice and administering the settlement. If this sounds ridiculous, it’s because there are nearly 50 million class members. The settlement administrators are going to try to mail all of them postcards with detachable claim forms and buy 180 million impressions on social media to let people know about the settlement. All in all, it’s a fairly cheap way — less than $0.50 per class member — to involve 50 million people in something.

The Anthem case is the most analogous to Equifax: names, dates of birth, Social Security numbers, and health care ID numbers were stolen, along with other data, which is why I think it’s a reasonable place to look for guidance on how the Equifax case will be resolved.

***

If you’re interested in more details, I have a thread on Twitter where I’m collecting analyses from security experts.