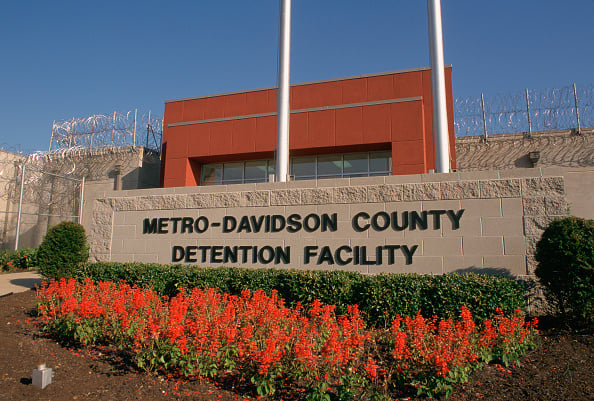

I was hopeful that Max’s Justice, USA, a six-part documentary series about Tennessee’s criminal justice system, would deliver its marketing promise of a “compelling, insider’s view of Nashville’s criminal justice system.” Sadly, it fell short.

There is some pedagogical value to shows such as Justice, USA, which provides access to men’s, women’s and juvenile jails, along with details that inmates and law enforcement struggle with, such as the effects of incarceration, mental illness and addiction. The series’ offer of a “360-degree” approach could go far in helping to educate viewers.

That sounds great in theory for those looking to understand the criminal justice system. But if you’re not involved with it, you don’t see what happens behind closed doors, and you don’t get a clear view.

And the incarcerated people’s stories will never go away, even if they get clean and turn their lives around. What’s on the internet and streaming services will live on forever.

Moreover, the series has thus far failed to explain some of the most counterintuitive aspects and sex-based discrepancies of American sentencing and incarceration.

Detained discrepancies

“Women, Incarcerated,” the fourth episode, piqued my interest. Since 2014, I’ve written about the astronomical number of incarcerated women in the United States specifically and my home state of Oklahoma generally.

According to the Prison Policy Initiative, as of March 5, there are 190,600 women and girls incarcerated in the United States. Over recent decades, women’s incarceration has increased at twice the pace of their male counterparts.

Over 25{c9b670b3c77d807bdd7060c9fc0a99121cc6b184676c9335f3481a95c383dd4c} of women who are incarcerated have not been convicted, and 60{c9b670b3c77d807bdd7060c9fc0a99121cc6b184676c9335f3481a95c383dd4c} of women in jails under local control (usually city or county jails) are incarcerated pending trial, as they are unable or decide not to post bail in their case.

But it’s not just the sheer number of women held in prisons and jails. Women have a higher mortality rate than men in jails; they die of drug and alcohol intoxication at twice the rate. Women are also more likely to become incarcerated with a preexisting medical issue or a mental health issue.

Different crimes, same times

Compared to men, women are often disproportionately charged and sentenced. For example, Oklahoma’s child abuse and neglect statute punishes mothers who arguably engage in child neglect, which is defined, among other things, as various omissions, such as failure to supervise, feed or provide children with enough nurturance and affection.

The statute also includes situations in which an adult doesn’t protect a child from exposure to illegal activities or sexual materials that are not age appropriate.

In the same vein, the “failure to protect” definition includes the conduct of a nonabusing parent or a guardian who “knows the identity of the abuser or the person neglecting the child but lies, conceals or fails to report the child abuse or neglect or otherwise take reasonable action to end the abuse or neglect.” Oddly, child neglect and child sexual abuse can both include life sentences.

Prosecutors have quite a bit of leeway when arguing the specific actions—or more often inactions.

The fifth episode of Justice, USA included the struggle that one inmate faced as she tried to live with herself through charges related to an overdose suffered by her toddler daughter after the child accidentally ingested some of her mother’s narcotics. The mother genuinely appears to love and miss her daughter, and the sorrow is evident. But her neglect as a drug addict kept her from protecting the toddler.

Situations such as that don’t have much middle ground. The mother’s recklessness still had a high likelihood of ending in tragedy. After all, the neglect was an obvious and apparent consequence of the mother’s failure to protect her child. That isn’t always the case for failure to protect and child neglect charges, though.

Take Tondalao Hall, for example.

An Oklahoma judge sentenced Hall to 30 years in prison because her boyfriend broke her child’s ribs and femur, and Hall “failed to stop him.” The boyfriend? He got two years.

Make that make sense to me.

Hall’s story was relayed by Samantha Michaels and published in Mother Jones in an excellent piece that highlights multiple Oklahoma women who suffered abuse at the hands of the men who ultimately abused their children, as well. Many of the women profiled received longer sentences than the men who actually physically abused the children.

I understand the position: As a society, we think that mothers should and will do anything in their power to protect their children. But what happens when the mother’s psyche is so destroyed by the abuse that she suffers that she can’t? The mind is powerful, but it can be damaged.

Maybe you argue that responsible women should never put their children in such a situation to begin with, or that she should just leave and take the kids. But ask yourself: Why would she stay if she really could leave? It’s a difficult question without an easy answer.

Questions such as these escape any analysis in Justice, USA. I understand if the series is restrained on how deep it can delve, but it’s a shame that it missed the chance to educate a huge audience on a systematic miscarriage of justice. If nothing else, the series was tailor-made for exploring the problem—at least from a surface level.

Things might start to change if the public has more exposure to the problem.

Adam Banner

Adam R. Banner is the founder and lead attorney of the Oklahoma Legal Group, a criminal defense law firm in Oklahoma City. His practice focuses solely on state and federal criminal defense. He represents the accused against allegations of sex crimes, violent crimes, drug crimes and white-collar crimes.

The study of law isn’t for everyone, yet its practice and procedure seems to permeate pop culture at an increasing rate. This column is about the intersection of law and pop culture in an attempt to separate the real from the ridiculous.

This column reflects the opinions of the author and not necessarily the views of the ABA Journal—or the American Bar Association.