The American Revolution was not merely a clash over taxation without representation, but a rejection of a deeply entrenched economic system that positioned Britain as the mother country, exploiting its colonies to amass wealth and power.

This system called “mercantilism” was a dominant economic theory in Europe from the 16th to the 18th century. It used state power in an attempt to accumulate wealth for the nation and its favored businesses.

One of the key principles of mercantilism was maintaining a positive balance of trade with more exports than imports. To this end, the government aggressively intervened in the economy by levying high tariffs, restricting trade with various countries, granting monopolies, and subsidizing favored industries.

Mercantilism reached its heyday in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries. Economist Murray Rothbard described it as “a system of statism which employed economic fallacy to build up a structure of imperial state power, as well as special subsidy and monopolistic privilege to individuals or groups favored by the state.”

Mercantilism was similar to what people today call crony capitalism. As Rothbard pointed out, it was as much a political as an economic system.

“The mercantilist writers, indeed, did not consider themselves economic theorists, but practical men of affairs who argued and pamphleteered for specific economic policies, generally for policies which would subsidize activities or companies in which those writers were interested. … At the same time, the network of regulation and its enforcement built up the state bureaucracy as well as national and imperial power.”

That’s exactly how it played out in the years leading up to the American Revolution.

While the conventional wisdom teaches that the colonists went to war with Great Britain due to “taxation without representation,” that was only one symptom of a much bigger problem – the British assertion that Parliament had power over the people “in all cases whatsoever.”

This played out most dramatically in the colonies’ economic affairs. Taxation without representation was part of a much broader, and long-standing mercantilist economic policy the British imposed on the colonies.

Colonialism was a hallmark of British mercantilism. Colonies were often established to serve merely as a source of raw materials that could be shipped to the mother country where they were formed into finished manufactured goods.

That’s just how the British generally treated its American colonies for over a century.

Benjamin Franklin lamented the way the mother country treated her colonies in a 1760 pamphlet titled The Interests of Great Britain Considered.

“The colonies must not only be devoted to, but dependent upon the mother country; their interest being, as it were, but a part of hers; and they, with respect to her, in the same state of a farm, with regard to the proprietor, which must yield all its produce to his advantage.”

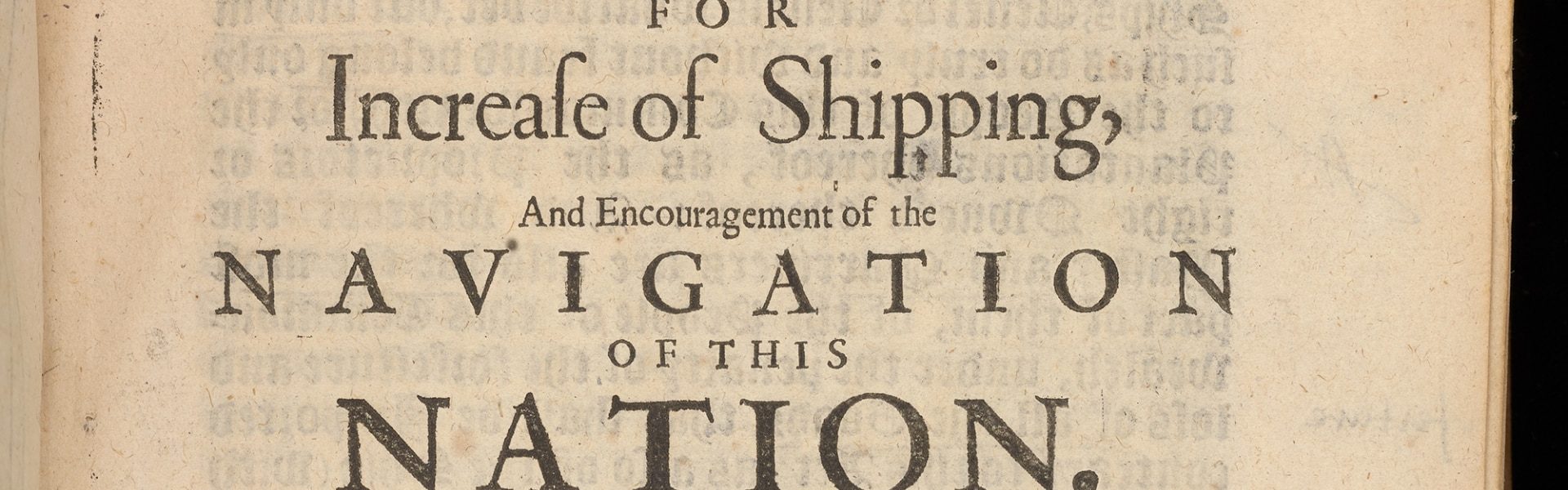

EARLY NAVIGATION ACTS

As the economies in the American colonies grew, it became imperative for Britain to limit manufacturing, and exports from the colonies. This resulted in a number of acts that colonists believed violated their autonomy.

Some of the first mercantilist acts imposed by the British were a series of navigation acts imposed between 1651 and 1673. These laws restricted colonial trade by requiring that all goods imported to or exported from the colonies must be transported on British ships.

These early Navigation Acts also mandated certain products including tobacco and sugar could only be shipped to England or other British colonies. For instance, the Navigation Act of 1651 prohibited both the import and export of salted fish in foreign ships.

In effect, they barred Americans from directly trading with other nations.

WOOL, MOLASSES, IRON

Parliament passed other acts that were purely mercantilist in nature. For instance, the Wool Act of 1699 prohibited the export of woolen products to any destination outside the colony in which they were produced, including other British colonies. It was intended to prevent the colonies from competing with domestic British wool production.

In 1733, Parliament passed the Molasses Act, levying a high tax on molasses, sugar, and rum imported into the colonies from non-British colonies. The tax was designed to make sugar and rum produced in the British West Indies cheaper compared with foreign products. In practice, it granted a de facto monopoly to British producers.

The Iron Act of 1750 restricted the establishment of new iron mills and steel furnaces in the American colonies. This policy forced the colonies to export raw iron to Britain where it was forged into finished goods. Those goods were then shipped back to the colonies at a higher cost than if they had been produced domestically. This ensured the colonies would remain a resource provider and not a manufacturer in their own right.

ENFORCEMENT

All of these restrictions on trade led to another problem – they needed to be enforced.

As a result, the British sent customs agents to the colonies armed with “writs of assistance.”

These were essentially open-ended search warrants authorizing the holder to search businesses and private homes for smuggled goods.

Writs of assistance did not require any specifications about the place to be searched or what types of goods the agents were looking for. Writs of assistance never expired and were considered a valid substitute for specific search warrants. They were also transferable.

When Parliament passed the Molasses Act, British customs officials became more aggressive in their battle against smuggling and ramped up the use of the hated writs of assistance. This led to one of the first legal battles with the colonists.

In 1761, James Otis Jr. took up a case against the writs, arguing they violated the unwritten British constitution and the rights of the colonists. In his nearly five-hour oration, Otis proclaimed, “A man is accountable to no person for his doings …one of the most essential branches of English liberty is the freedom of one’s house.”

Otis also emphatically asserted that these “general warrants” were a constitutional issue, proclaiming, “An act against the constitution is void,” and he went on to insist that “special warrants only are legal.”

Otis lost the case, but it was a spark that eventually grew into the flames of independence.

John Adams later wrote, “American independence was then and there born. The seeds of patriots and heroes, to defend the vigorous youth, were then and there sown. Every man of an immense crowded audience appeared to me to go away as I did, ready to take arms against writs of assistance…Mr. Otis’s oration against Writs of Assistance, breathed into this nation the breath of life.”

SUGAR AND STAMPS

Undeterred, Parliament continued to pass laws supporting its mercantilist aims.

In 1764, it imposed the Sugar Act, reducing the tax on molasses but ratcheting up enforcement measures to prevent smuggling. It also expanded the list of taxable items to include wine, silk, indigo, coffee, and other products. The stricter enforcement directly undermined the profitability of colonial merchants.

Because colonies primarily serve as a source of raw materials in a mercantilist system, it is easy for government officials to begin to view colonists as tax cattle as well as resource producers. Buried under a heavy load of debt after a long war with France, the king and Parliament began to view the American colonies as a source of income as well as materials.

This led to the passage of the Stamp Act in 1765, the first internal tax levied directly on the American colonies.

The act required all official documents in the colonies to be printed on special stamped paper. This included all commercial and legal documents, newspapers, pamphlets, and even playing cards.

The American colonists argued that the Stamp Act violated the bounds of the British constitutional system. Objecting to the notion that Parliament could impose whatever binding legislation it wished upon the colonies, the Americans adopted a rigid stance asserting that colonists could only be taxed internally by their local assemblies. They claimed this principle stretched back to 1215 and the Magna Carta.

TOWNSHEND AND TEA

Protests and mass non-compliance forced the British to repeal the Stamp Act, but Parliament doubled down with the passage of the Declaratory Act asserting that it had the authority to legislate “in all cases whatsoever.”

It then put this into practice when it levied new taxes on the colonies with the passage of the Townshend Acts in 1767, imposing duties on imported goods including glass, paper, paint, and tea. It also further expanded British powers to prevent smuggling. These taxes were not only a revenue source for the British, but they also served to protect domestic manufacturing and trade.

But for the colonists, it meant higher prices and shortages.

In a 1769 essay titled “An Appeal to the World,” Samuel Adams summarized the economic grievances piled on by these mercantilist policies.

“The trade of the colonies has been greatly embarrassed and obstructed by several acts of parliament, by which large duties are laid on almost all articles of importation from Great Britain. This is esteemed a grievance, inasmuch as the colonists have no representatives in parliament.”

The Townshend Acts also included the New York Restraining Act, giving the royal governor the authority to suspend the Assembly of New York because it refused to authorize funding to provide housing, food, and other necessities for British troops as required under the 1765 “Quartering Act.” The assembly’s refusal to cooperate was an example of passive resistance that the colonists would turn to with increasing frequency as the British attempted to assert more and more power over the colonies.

In 1773, Parliament passed the Tea Act granting the British East India Company the exclusive right to sell its surplus tea directly to the colonies, bypassing colonial tea merchants. It also authorized this state-supported monopoly to sell tea at a reduced price.

As the Boston Tea Party Museum explains, it was essentially a government bailout for the East India Company.

“The British East India Company was suffering from massive amounts of debts incurred primarily from annual contractual payments due to the British government totaling £400,000 per year. Additionally, the British East India Company was suffering financially as a result of unstable political and economic issues in India, and European markets were weak due to debts from the French and Indian War among other things.”

The Tea Act was the straw that broke the camel’s back and resulted in what we call the Boston Tea Party today.

It was the culmination of a long series of mercantilist policies that the colonists perceived as exploitative and unjust. They fueled colonial resentment and a sense of economic and political oppression, setting the stage for the War for Independence.